I love world cultures! My curiosity over years has made me spend a lot of my time conducting self-studies on various cultures, their rituals, customs, and of course, jewelry. I hope you enjoy my curated list of Mughal jewelry and artifacts in this blog post!

I have tried my best to attribute images to their creators and original sources. Please contact me if you know the source of images that are not attributed.

Mughal emperors were lovers of precious stones, numerous references show the strong cultural belief in gemstone properties. The Timurids, ancestors of the Mughals, had begun the tradition of engraving titles and names on stones of outstanding quality and, along with diamonds and emeralds, large spinel beads were their favorite. As much as these gems were a symbol of the opulence and dignity of the empire, they were also treasured as protective talismans.

Emeralds were enormously popular with the Mughal Court, whose emperors referred to them as “Tears of the Moon” because of their opaque transparency.

One of the most treasured jewel in Indian history: The Taj Mahal Emerald. Circa 1630-1650. A hexagonal-cut emerald, weighing approximately 141.13 carats, it is carved with stylized chrysanthemum, lotus and Mughal poppy flowers, within asymmetrical foliage, to the plain reverse and beveled border. This intricately carved stone is one of a small group of exquisite emeralds commissioned by the Mughal Court, possibly during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan. The name of the emerald is derived from its intricately carved surface of lotus, poppy flowers, and other foliage that mirrors the decoration of the Taj Mahal. At the Paris Exhibition of 1925, 'The Taj Mahal Emerald' was one of three large Mughal emeralds that featured prominently in Cartier’s Collier Bérénice, a spectacular shoulder ornament that also boasted pearls, diamonds, and black enamel.

The Taj Mahal Emerald, Cartier. Hexagonal-shaped carved tablet emerald of 141.13 carats, circular-cut diamonds, platinum and 18k white gold. Mount by Cartier. Image: Christie’s

The rulers of Mughal India often ordered their names and titles to be inscribed on rubies, emeralds and diamonds, a practice which originated in Iran under the Timurids (1370-1507). Some of these gems ended up in the collection of the Mughal emperors who continued the tradition. In some cases, as the gems were passed down further names were added below those of the previous owners. Many were repolished, recut and re-set as they were handed down. The inscriptions were executed using the traditional cutting wheel or diamond-tipped stylus.

The rectangular-cut emerald known as 'The Mogul Mughal' weighing 217.80 carats. It's a magnificent emerald with a great back story! Carved emerald with a Shi`ite invocation; Mughal or Deccani, 1695-1696. The reverse carved all over with foliate decoration, the central rosette flanked by single large poppy flowers, with a line of three smaller poppy flowers either side, the bevelled edges carved with cross pattern incisions and herringbone decoration, each of the four sides drilled for attachments, 2 1/16 x 1 9/16 x 7/16 in. (5.2 x 4x 1.2 cm.) Originally mined in Colombia, it was sold in India, where emeralds were much desired by the rulers of the Mughal Empire.

This magnificent, rectangular-cut emerald bears the inscription “Jahangir Shah-i Akbar Shah” and the year 1018 AH (1609-1610 CE) in its centre, and is the only known inscribed and dated Mughal emerald from the reign of the Emperor Jahangir (r. 1014-1037 AH/1605-1627 CE). Usually adorned with Qur'anic verses, mystical sayings, or pious formulas, emeralds – unlike spinels, which were often inscribed with royal titles – were rarely engraved with the names of their sovereigns. The tradition of inscribing stones with royal titles was inherited by the Mughals from their ancestors, the Timurids, and dates back to the 14th century. Believed to possess various healing powers, emeralds were often worn to repel illnesses and evil spirits. Image copyright: The Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar.

Turban Ornament Ca. 1733 to 1767 CE Gold, Enamel, Emerald, Diamond. Image copyright: The Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar.

The 17th century jewel-encrusted spectacles, which feature lenses made from diamond and emerald rather than glass, are believed to have originally belonged to royals in the Mughal Empire, which once ruled over the Indian subcontinent. The green lenses spectacles dubbed the "Gate of Paradise," are believed to have been cut from a Colombian emerald weighing over 300 carats. Any gemstone of this size, magnitude or value would have been brought straight to the Mughal court. Image: Sotheby’s, 2021 / Source: CNN

According to Sotheby's, a story surrounds Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, who is said to have used emeralds to soothe his tired eyes after weeping for days following the death of his wife Mumtaz Mahal (for whom he built the Taj Mahal as a tomb).

The 17th century jewel-encrusted spectacles, which feature lenses made from diamond and emerald rather than glass, are believed to have originally belonged to royals in the Mughal Empire. The lenses in one pair, known as the "Halo of Light" spectacles, are believed to have been cleaved from a single 200-carat diamond found in Golconda, a region in the present-day Indian states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. The green lenses spectacles dubbed the "Gate of Paradise," are believed to have been cut from a Colombian emerald weighing over 300 carats. Any gemstone of this size, magnitude or value would have been brought straight to the Mughal court. Image: Sotheby’s, 2021 / Source: CNN

The 17th century lenses in this pair, known as the "Halo of Light" spectacles, are believed to have been cleaved from a single 200-carat diamond found in Golconda. Any gemstone of this size, magnitude or value would have been brought straight to the Mughal court. Image: Sotheby’s, 2021 / Source: CNN

The Halqeh-e Nur or the "Halo of Light" spectacles, are believed to have been cleaved from a single 200-carat diamond found in Golconda in the 17th century. The frame was made in the 19th century. Any gemstone of this size, magnitude or value would have been brought straight to the Mughal court. Image: William Dalrymple Twitter.

The Shah Jahan Emerald.

North India or Deccan, dated AH 1031 (1621–22)

Inscribed in Persian: Shihab al-din Muhammad Shah Jahan Padshah Ghazi 1031 (“Shihab al-din Muhammad Shah Jahan Ghazi Emperor 1031”). Usually adorned with pious formulas, Koranic verses or mystical sayings, emeralds – unlike spinels or balas rubies often inscribed with royal titles – were rarely engraved with the names of the sovereigns who owned them, hence the singularity of this cabochon-cut emerald bearing the name of Shah Jahan. Image courtesy: Al Thani Collection

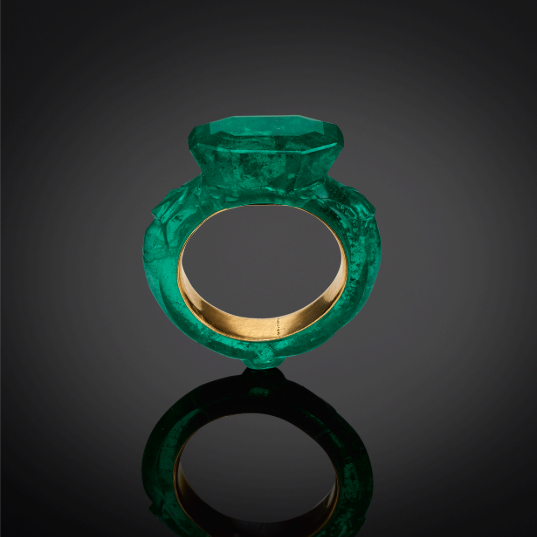

A colossal sole emerald carved into a ring! With a sleeve of gold (later addition). 16th century, India. Verdant Colombian emeralds were revered by the Mughal Emperors and symbolized the force of life. Image: Al Thani Collection / Christie's. Today, it will be very difficult to find an enormous size and quality of emerald (such as this) to be carved into one sole ring. This is an epic piece of gemological and Mughal history.

Ring. India, sixteenth century. Emerald, with gold sleeve. Image courtesy: Al Thani Collection

An emerald, diamond and seed pearl necklace, Colombian emeralds, mid- to late-19th century. Image: Christie’s

Brooch, carved emerald from Mughal India is set in a jeweled platinum mount produced in the early twentieth century by Cartier in New York. Image: The Metropolitan Museu

Detail. Brooch, carved emerald from Mughal India is set in a jeweled platinum mount produced in the early twentieth century by Cartier in New York. Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Inlaid emeralds necklace with rubies, diamonds. Mughal Indian work of the 18th-19th century, mounted by Cartier in the 1930s. Image credit: British Museum

Details. Inlaid emeralds necklace with rubies, diamonds. Mughal Indian work of the 18th-19th century, mounted by Cartier in the 1930s. Image credit: British Museum

The legendary Koh-i-Noor Diamond - a gemstone that witnessed Mughal history

The Koh-i-Noor was set in the Peacock Throne, the world’s most expensive gem-set throne. Set atop the Peacock Throne, the Koh-i-Noor witnessed reigns of many Mughal emperors - Shah Jahan (commissioned the Peacock Throne in 1628), Aurangzeb, Bahadur Shah I, Jahandar Shah, Farrukhsiyar, Rafi Ul-Darjat, Rafi Ud-Daulat, Nikusiyar, Muhammad Ibrahim and Muhammad Shah ‘Rangila’, who eventually lost the Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor diamond in an invasion-loot by Nader Shah of Persia in 1739.

The Peacock Throne (Hindustani: Mayūrāsana, Sanskrit: मयूरासन, Urdu: تخت طاؤس, Persian: تخت طاووس, Takht-i Tāvūs)

Portrait of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan on the bejewelled Peacock Throne. 19th century. Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Image of Koh-i-Noor added by Reena Ahluwalia for this educational blog). In 1628, Mughal ruler Shah Jahan commissioned this magnificent, gemstone-encrusted throne. Among the many precious stones that adorned the throne were two particularly enormous gems that would, in time, become the most valued of all: the Timur Ruby—more highly valued by the Mughals because they preferred colored stones—and the Koh-i-Noor diamond. According to eyewitness account of Persian historian, Muhammad Kazim Marvi, of the 1739 invasion of Northern India by Nader Shah, Marvi notes: “On top of this was placed a peacock made of emeralds and rubies; on to its head was attached a diamond the size of a hen’s egg, known as the Koh-i-Noor – the Mountain of Light.”

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond, meaning "Mountain of Light" in Persian, is a legendary diamond of Indian origin. The diamond has been a subject of desire, intrigue and conquests for centuries. A widely traveled gem, it has passed through the hands of the Mughals emperors, Persian Shahs, Emirs of Afghanistan and Maharajas of Punjab. The stone later ended up in the British Crown Jewels in 1849, when a ten-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh was persuaded to hand over the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria when the Punjab Region of India was annexed. Since then, Koh-i-Noor has remained in the British Crown Jewels, becoming a symbol that many attach to the humiliation and pain of colonial past, conquests and the British Raj.

The world’s most famous, Koh-i-Noor is a diamond of monumental stature. Image: Compliled by Reena Ahluwalia, with Reena’s painting of the Koh-i-Noor diamond at it’s center.

The Arcot II Diamond. Pear brilliant-cut diamond of 17.21 carats. The Arcot Diamond, a D-colour stone was one of two such diamond ear drops sent as gifts to Queen Charlotte (1744-1818), the wife of King George III, from the Nawab of Arcot. The diamonds were later acquired at auction by the Marquess of Westminster and subsequently mounted in the Westminster Tiara, which was worn at the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Image: Christie’s

The Nizam of Hyderabad Necklace. Diamond, emerald and enamel necklace. The eight modified triangular-shaped table-cut golconda diamonds, variously-shaped faceted and rose-cut diamonds, carved emerald bead, green enamel, foil, gold, engraved on the reverse with foliate motif, 16 in, late 19th century. The modified brilliant-cut of these diamonds reflect the advancement of gem faceting in India. Additionally, the openwork setting and symmetrical nature of the necklace's design is the direct result of Western influence. Image: Christie’s

Wine cup made for the Emperor Shah Jahan, 1657, India, white nephrite jade. Museum no. IS.12-1962, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. This unique wine cup of white nephrite jade is an outstanding example of jade craftsmanship and is one of the most exquisite surviving objects from the court of the Mughal dynasty that ruled the Indian subcontinent from about 1526 to 1857. The cup was made in 1657 for Shah Jahan who ruled the Mughal Empire from 1628 to 1658.

The wine cup of Shah Jahan

The cup consists of a gourd shape with a handle shaped like the head of a ram. The base features acanthus leaves radiating out from a lotus flower which is raised to form a pedestal for the cup. The different features of the cup reflect the variety of cultural and artistic influences that were welcomed at the Mughal court. Persian in their cultural background and Indian by adoption, the Mughals were also open to new ideas from the West. Jesuits at the Mughal court, entertaining futile ideas of converting an Empire, were welcomed for their learning; ambassadors and merchants for their exotic gifts and promises of trade. Craftsmen-adventurers were especially welcomed for their skills and knowledge of unfamiliar technologies.

Wine cup made for the Emperor Shah Jahan, 1657, India, white nephrite jade. Museum no. IS.12-1962, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The use of a gourd form for the body of the cup is Chinese in inspiration, while the lotus petals and sensitivity of animal portraiture are characteristic features of Hindu art. The ideas of the pedestal support and the use of acanthus leaves are also European in origin and parallel similar elements in the decoration of Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan's reign.

An enamelled and gem set model of a parrot, Hyderabad, Deccan, circa 1775-1825. Set with diamonds, rubies and emeralds and with a pendant emerald hanging from its beak, on a stand similarly decorated, base decorated with two central flowers in green and white enamel and four leaves in each corner. Image: Christie’s

A Mughal cut-cornered rectangular portrait-cut Golconda diamond of 20.22 carats, Type IIa. The present diamond also exhibits a feature common in gems shaped for Mughal use, a pair of drilled holes by which a stone could be sewn to a turban or garment to impart both pomp and courtly fashion. Image: Christie’s.

Portrait diamonds, also called lasques, are among the earliest cut diamonds preserved to this day. Extremely shallow, they consist of virtually nothing but two tables separated by a tiny row of girdle facets. They were sometimes used to cover miniature paintings and therefore came to be known as portrait diamonds. Due to their extreme flatness, they were unsuited for later recutting and their original shape was preserved, making them historically significant.

Large portrait diamonds are extremely rare and among few famous examples is one seen on a portrait of Shah Jahan from 1616, where he holds a turban ornament set with an emerald and a portrait diamond or the ‘Russian Portrait Diamond’, dating around 1820, covering a miniature portrait of Czar Alexander I in a bracelet.

This carved flat emerald is set in a platinum, gold, and diamond pendant necklace. The emerald was discovered in Colombia, possibly by Spanish conquistadors, and found its way to India for cutting. Smithsonian, photography by Ken Larsen.

Historic and remarkable Mughal Emerald necklace. Small drill holes in the sides of the emerald, possibly used to attach the stone to a cloak or turban, also are consistent with a Mogul origin. The emerald is surrounded by round diamonds and is suspended from a double row diamond necklace; the diamonds total approximately 50 carats. A hallmark indicates that the Mogul emerald was set into the pendant and necklace in France around the turn of the 20th century. Smithsonian, photography by Ken Larsen.

A Mughal carved emerald pendant set with enamelled parrot-shaped mounts, India, 19th century, with later pearl necklace. Previously in the family collection of Shaikh Gholam Muhyi ad-Din, Governor of Kashmir (1832-45). Image: Sotheby’s.

Marjorie Merriweather Post’s platinum brooch from the 1920s, featuring a spectacular 60-ct. carved Mughal emerald surrounded by diamonds.

An inscribed Mughal emerald personal seal set in a diamond encrusted gold bangle and bearing the name of Major Alexander Hannay, an East India Company officer. Photo Bonhams

Mughal emerald and diamond sarpech. Mid-18th century. 78 emeralds are of Colombian origin. Photo: Christie's

Spinels (balas rubies) were highly prized in the Mughal court and were usually drilled as beads and used as pendant gemstones on necklaces, turban ornaments or earrings. Abu'l Fazl treasury historic records indicate a hierarchy of gems where spinels were listed in advance of diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds. They were admired for their colour which followed the Persian literary tradition of representing wine and the sun, evoking the light of dusk.

Tavernier reported that he counted 108 large balas rubies (spinels, it is believed) mounted on the famous Peacock Throne, all cabochon cut, the smallest weighing about 100 carats and some 200 carats or more.

A 128.10 carat inscribed Mughal Spinel Bead. Engraved 'Jahangir Shah Akbar Shah', dated 'AH 1018/1609-10 AD', and 'Shah Jahan, Jahangir Shah', dated 'AH 1049/1639-40 AD', to the fabric torsade necklace. Jahangir was a great connoisseur of gems. He was described by a contemporary English visitor, the Rev. Edward Terry, as ‘the greatest and richest master of precious stones that inhabits the whole Earth’. His passion for gems was continued by his son, Shah Jahan. The origin of the spinel is Tajikistan, with no indications of heating. Together with the historical context of such spinels, this jewel can be considered a true treasure of nature. Image: Christie's (2016)

An Imperial Mughal spinel necklace with eleven polished baroque spinels for a total weight of 1,131.59 carats. Three of the spinels are engraved. Two with the name of Emperor Jahangir (1569-1627), one with the three names of Emperor Jahangir, Emperor Shah Jahan and Emperor Alamgir, also known as Aurangzeb.

Inscribed royal spinel (balas ruby) weighing 249.3 carats. This majestic stone is inscribed with the names of its six imperial owners and has the distinction of having the second-most number of such inscriptions. It was a gift from the Safavid Shah Abbas the Great of Iran to the Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1621. Image courtesy of © The Al-Sabah Collection.

Rulers mentioned in inscriptions:

1. Timurid, Ulugh Beg (before 1449)

2. Safavid, Shah Abbas I (1617)

3. Mughal, Jahangir (1621)

4. Mughal, Shah Jahan (undated)

5. Mughal, Alamgir (Aurangzeb) (1659 – 1660)

6. Durrani, Ahmad Shah (1754 – 1755)

Detail: Inscription on an Imperial Mughal spinel necklace. These spinels mainly originated from the Badakhshan mine, in the 'Pamir' region (on the frontier between Afghanistan and Tajikistan). This province gave its derived name to spinels, described as 'Balas rubies' for decades.

Ring with Shah Jahan’s Spinel

North India, the spinel dated AH 1053 (AD 1643– 44); the ring, c. 1900Gold with enamel, the spinel inscribed in Persian: Sahib qiran-i thani (“Second Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction”)

Dating from 1643, this spinel is engraved on the reverse “Sahib qiran-I thani” which translates as “Second Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction”, the title of Emperor Shah Jahan who ruled 1628 - 1658. The title was chosen by Shah Jahan himself in reference to Timur (Tamerlane), the Mughals’ dynastic ancestor, who bore the title “Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction”. It is most likely that the engraving on the spinel was also the sovereign’s personal seal. Image courtesy: © The Al Thani Collection

The Taj Mahal Diamond [circa 1621] - a diamond with extraordinary provenance! Owned by Jahangir, ruler of Mughal India and father of Shah Jahan who built the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal diamond was gifted by Richard Burton to Elizabeth Taylor for her 40th birthday. Diamond is inscribed in Arabic on either side.

Legendary Taj Mahal Diamond. I was fortunate to privately view and hold this diamond in the palm of my hand at Christie's New York in December 2011. It's an incredibly piece of diamond history.

This massive Mughal baroque pearl must have been prized for its size and perfectly imperfect shape. It was drilled for suspension as a pendant, perhaps from a necklace, and given a decorative gold setting in the form of petals that were originally enamelled. Marks in the gold cap of the pearl have been read as the number 982, and interpreted as representing a year, corresponding to 1574-75 CE, which falls during the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556-1605 CE). Image, copyright: The Museum of Islamic Art, Qatar.

Rare image of Mughal Coins. Mughal emperors. Photo: The David Collection

Gold coin of Emperor Jahangir. Ajmer. Ninth year of reign. 20.5 mm. On deposit from Christ Church, Oxford. Credit: Ashmolean Museum

The Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–27) showed exceptional engagement with his coinage, which represents the height of Mughal Indian numismatic art in calligraphy and design. The front of this example features a portrait of Jahangir sitting cross-legged, reclining against a bolster on a hexagonal throne and holding a goblet-like ornament in his hand. It has been described as a wine goblet, showing the Emperor's attachment to his favourite pastime. The Farsi inscription around the portrait reads, ‘Destiny has made the picture of a likeness of venerable king Jahangir on this gold coin’. Jahangir issued coins bearing his portrait, by his own admission, to be given to his followers as a special gift which they could ‘wear on their turbans or sashes’ to show that they had been graced by imperial favour.

Reverse. Gold coin of Emperor Jahangir. Ajmer. Ninth year of reign. 20.5 mm. On deposit from Christ Church, Oxford. Credit: Ashmolean Museum.

On the reverse is a central sun burst with compartments on either side. The one on the left mentions Ajmer as the place where the coin was made (Jahangir had moved his court there in 1615–19 and 1023, the Islamic (Hijri) year of its issue. On the right are the words ‘O Assister’, followed by ‘Year 9’, the year of the reign. The Farsi inscription reads ‘The words “Jahangir” and “Allahu Akbar” are equal in value till the Day of Judgement’. Based on the so-called Abjad system, which applied numerical value to each letter of the alphabet, the words ‘Jahangir’ and ‘Allahu Akbar’ (‘Allah is greater’) were considered to add up to the same total.

Gold coin. (whole) Lion surmounted by sun. (reverse) Portrait of Jahangir. (obverse). AD 1611. Credit: The British Museum.

Mughal gold coin, issued by Jahangir. Constellation of Tora (Taurus)/Vrishabha. AD 1605-1627. Image credit: Classical Numismatic Group.

Jahangir (1605-1628), Emperor Akbar’s son and immediate successor, used the Ilahi Era to great artistic effect by issuing two series of mohurs that incorporated Ilahi Era elements. The earliest series, known as the portrait series, since the coins show the emperor on the obverse, all show the constellation Leo superimposed over the sun – a reference to Jahangir’s birth in August. This series was struck within a three-year span early in Jahangir’s reign and are quite rare. The second series, known as the zodiac series, since each of the twelve constellations of the Zodiac is represented on the reverse, was a much larger series. Struck both in gold and silver, the zodiac series was issued from several mints (with Agra being the primary), and like the previous series, minted over three or four years. Since the Ilahi months were solar months and corresponded with the solar ecliptic (an imaginary line in the sky that marks the annual path of the sun), each month was represented by an appropriate sign of the Zodiac, recording its particular month of issue. Because many of these coins had been recalled and melted by Jahangir’s successor, Shah Jahan, original strikes are very rare.

“Previously to this, the rule of the coinage was that on the face of the metal they stamped my name, and on the reverse the name of the place and the year of the reign. At this time it entered my mind that in place of the month they should substitute the figure of the constellation which belonged to that month...in each month that was struck, the figure of the constellation was to be on one face, as if the sun was emerging from it.” ~ The Memoirs of Jahangir [Tuzk-e Jahangiri] (Entry for 20 March 1619)

Gold Zodiac coins / Gold dinars of Jahangir. Credit: Ashmolean Museum

The powder flask was an essential firearm accessory and held the fine powder needed to make the gun fire. Gunmakers in India during the Mughal era (1526-1858) specialized in carving ivory powder flasks with animal figures. Often, as this example, the decoration consists of intertwined and composite creatures that seem to grow out of or attack one another. 18th century. Note: International trade in ivory is banned (The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

An unusual ivory Archer's Ring in the form of a Falcon probably Mughal, 18th Century formed by a three dimensional bird with ruby-set eyes and folded wings. Photo: Bonhams.

A rare Mughal archers thumb-ring of hippo ivory, India, 17th/18th Century. Sotheby's

Jade archer's thumb-ring. Mughal dynasty, 17th century AD. India. British Museum

1650. Thumb rings of this type were originally used in archery as a way of releasing the bow-string accurately without injuring the hand. Thumb rings made with precious materials became objects of royal status in the Mughal courts of India. Photo: V&A

Dress archery ring of Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan. Second quarter of the 17th century. Gold set with carved and polished uncut diamonds, rubies and emeralds. Photo: State Hermitage Museum.

A Mughal carved emerald flask with stopper, India, circa 18th century. The body of faceted hexagonal form, cut and carved on each face with a floral stem, the stopper carved with eight stylised leaves and a star design to the top. Sotheby's

Engraved Emerald Gem Set box. 16 century Mughal India. Image copyright: The Museum of Islamic art. Qatar.

Emerald-ser box, Mughal India. 1635. Gold sheet, set with carved Colombian emeralds and a faceted diamond in gold kundan, with an enamelled base. The sides and lid of this spectacular gold box are set with 103 emeralds, perfectly matched and fitted. They are carved in shallow relief to depict cypress trees within borders of repeated stylized leaves. Similar boxes made of various precious materials appear in Indian miniatures from the early 17th century on. They could have been for medicines (including opium, a Mughal panacea) or to hold even more precious objects, such as uncut diamonds. The decoration suggests European influence, which presumably came into Mughal court art during the first half of the 17th century with the European craftsmen in the service of Jahangir and Shah Jahan. It is possible that the designs were influenced by engravings from the studio of Bernard Salomon who worked at Lyons in the mid-16th century. Image: The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art

Mango-shaped scent bottle Mid-17th century Rock crystal with rubies and emeralds set in gold. Mughal India. Image: Asia Society

Mango-Shaped Flask, mid-17th century India Rock crystal, gold and gemstone inlay. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mango-shaped container, rock crystal, inlaid with gold and rubies. India, Mughal; 17th century. The princes of the Mughal dynasty had a special love for semi-precious stones like jade and rock crystal, and their artists achieved a very high degree of perfection in carving objects such as dagger hilts, bowls, and rings from these materials. Grooves cut into the materials could then be inlaid with gemstones and gold. Photo: The David Collection

Holding Mughal history in my hand at the Natural History Museum, London! A rare private viewing from the vaults of NHM of a 31-ct., faceted 'rose cut' #sapphire in a Quartz 'rock crystal' button inlaid with gold, rubies, emeralds. Purchased by Sir Hans Sloane for £43 (!), late 17th century. Image credit: Taken by Reena Ahluwalia at the Natural History Museum, London. 2016

Claude Martin's Mughal Dagger. The hilt of this magnificent Mughal dagger is fashioned from rock crystal inlaid with gold and set with rubies, emeralds and diamonds. The dagger was formerly owned by Claude Martin, one of the most prominent East India Company officials. It was under his patronage that great Lucknavi artists, such as Bahadur Singh and Mihr Chand, combined their Mughal training with European conventions and materials to produce innovative works of art. Image credit: The Wallace Collection

Details. Claude Martin's Mughal Dagger. Image credit: The Wallace Collection

Details. Claude Martin's Mughal Dagger. Image credit: The Wallace Collection

Details. Claude Martin's Mughal Dagger. Image credit: The Wallace Collection

Details. Claude Martin's Mughal Dagger. Image credit: The Wallace Collection

Crown of the Emperor Bahadur Shah II (the last Mughal emperor). 1850. Gold, turquoises, rubies, diamonds, pearls, emeralds, feathers and velvet. The Royal Collection©

A Mughal gem-set silver and gold rosewater sprinkler. North India, , 17th/18th century. Photo: Christie's

An Indian gem-set gilt-metal casket with bird-head finial. Mughal, India. Photo: Sotheby's

A Mughal-style gemstone-encrusted white jade scent bottle. 18th/19th century. Of flattened circular shape on a short oval foot, the cylindrical neck fitted with a screw-top cover with a knop finial, the body inlaid in gold and inset with gem stones including diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds, depicting two panels on the front and back enclosing birds and blossoming branches, the sides with further blossoms.

Highly detailed plate. 17th century, Mughal India. Gold, kundan setting technique, uncut diamonds, rubies, emeralds and enamel. Presented by the ambassadorial mission of Iranian ruler Nadir-Shah to the Russian Imperial Court, 1741. Photo: State Hermitage Museum.

A diamond-inset and enamelled bowl and stand. Deccan or Mughal India, late 18th century. Photo: Christie's

Dish, colorless glass, decorated with enamel and gilded. India, Mughal; c. 1700. The flowers on the dish were contoured on the inside with gold and filled in with red and yellow enamel, while the outside was painted solely in yellow. This produces a kind of three-dimensional effect that is characteristic of Mughal glass art with painted decoration. Photo: The David Collection

Turban ornament. 1700-1750. Wearing plumes in a turban indicated royal status in Mughal India. Nephrite jade, gold inset with rubies, emeralds, probably topaz, with gold foil, rock crystal and pearl. Photo: V&A

Kundan set eagle pendant. Mughal, India. Rubies, diamonds, pearls, enamel. Photo: The Al-Sabah collection.

Mughal parrot finger ring (c.1600–1625) with a three-dimensional bird that can rotate and bob (possibly providing hours of entertainment for its owner) is set with rubies, emeralds, diamonds and a single sapphire. Photo: The Al-Sabah collection.

Bird Finger Ring (1st quarter of the 17th century), Indian, Mughal or Deccan - Gold, rubies, emeralds, turquoises; carving, kundan technique. Photo: The Al-Sabah collection.

Pendant in the form of an eagle, Mughal India, 18th century. Gold, cast and chased, set with foiled diamonds, rubies, emeralds, and sapphires in gold kundan. Photo: © Nour Foundation

This extraordinary figurine comes from the Mughal dynasty of India. Gold, pearl, ruby, diamond and enamel squatting duck on a stand. Photo: British Museum

Gold and enamel figurine of an elephant with large natural baroque pearl forming its back and diamonds on its head. Mughal, India. Image credit: British Museum

Golden spoon, quite literally!

A rare Mughal gem-set gold spoon, India, 17th-18th century. The back is delicately inlaid on the reverse with a lotus rosette comprised of radiating foil-backed diamond petals and rubies, the faceted tapering shaft inlaid with emeralds and bands of ruby quatrefoils within an engraved and chiseled gold framework. Photo: Sotheby's.

A Mughal masterpiece. The necklace features five pendant diamonds (Origin: Golconda mines, India) with emerald drops. The central stone weighs 28 cts. and is the largest table-cut diamond known. The five surrounding stones—weighing 96 cts. collectively—comprise the largest known Matching set of table-cut diamonds from the 17th century. It is believed that the jewel once belonged to a Mughal emperor.

Mughal ruler Shah Jahan's Wine Cup. Jade. 1657. Jade cup carved in the form of a shell or gourd with carved handle terminating in the head of an Ibex & large floret shaped foot, left side underside view. This large cup is the finest known example of Mughal jade-carving. The Emperor's titles are carved on its side along with the date. Source: V&A Museum

Huqqa (water pipe) of emerald-green glass decorated with gold and yellow enamel

Northern India; 1st half of 18th century.

The motif was painted “in reserve,” which means that the gold was largely used as the background for the motifs – poppies and cypresses along with various leaf borders. A few details, such as the ribs or little leaves, were executed in gold or yellow enamel. A special refinement is the use of enamel inside, behind the flower heads. Photo: The David Collection

Portrait of Mumtaz Mahal (Arjumand Banu Begum). She was the favourite wife of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. She died shortly after giving birth to her fourteenth child in 1631. The following year the emperor began work on the mausoleum that would house her body. The result was the world-famous Taj Mahal. Photo: V&A

Miniature portrait pendant. Watercolor on ivory, gold, glass. 1830-1850, India. In this instance, an artist from Delhi has portrayed a courtesan dressed as a princess wearing elaborate Mughal gold and gem-set jewelry. Photo: The Walters Art Museum

A Bejeweled Maiden with a Parakeet. Illustrated single work. ca. 1670–1700, Mughal. India, Golconda, Deccan. The bird sits on the maiden’s henna-reddened fingers, each one of which is separately adorned by a diamond ring. She also wears strands of pearls, with emeralds and rubies.

This sensitive portrait jewel was probably painted shortly after Shah Jahan came to the throne of the powerful Mughal Empire in 1628 after the death of his father, Jahangir. Hashim (Indian, active 1598-c.1650). Credit: Cleveland Art

Oval portrait of a woman in a Chaghtai hat c. 1740-50 India, Mughal, 18th century Opaque watercolor and gold on paper. This woman’s hat has been studded with jewels and strings of pearls. The portrait jewel format that was once reserved for the emperor has now been expanded to include ladies of the court. The woman holds a jade wine cup and wears a draped upper garment with a woven or embroidered border similar to the fragment on display at the left. Credit: Cleveland Art

Pomander. 17th-18th Century Indian, Mughal Spherical rock crystal cover with enameled silver mounts. This tiny pear-shaped vial worn tied to a sash would have held scented water or oil. The lid opens to reveal a perforated sprinkler decorated with fine filigree and colorful enamel. A popular scent was attar of roses, made from the essential oil of rose petals. Credit: Cleveland Art

This tiny pear-shaped vial worn tied to a sash would have held scented water or oil. The lid opens to reveal a perforated sprinkler decorated with fine filigree and colorful enamel. A popular scent was attar of roses, made from the essential oil of rose petals. Credit: Cleveland Art

Pendant 1700s. Gold, emerald, diamonds, enamel, and pearl. India, Mughal, Rajasthan, Jaipur, 18th century. Credit: Cleveland Art

A rare Mughal pale green jadeite snuff bottle. 1800-1900. The flattened, rounded bottle is well carved on either side with a large flower reserved on a dense ground of overlapping leaves. Either shoulder is carved with a smaller flower head as is the top of the mouth rim. The translucent stone is of pale icy green tone. 2 in. (5 cm.) high, pink tourmaline stopper and bone spoon.

Mughal gold and enamel belt buckle in two pieces with inlaid diamonds. Enamel decoration on reverse of tiger attacking a boar. b. Rectangular element with small round ring through which oblong ring fits. Hook is attached to this. Enamel tiger attacking a deer in foliage on reverse of rectangular element. British Museum

Gold and enamel figurine of bird on a stand, set with diamonds, with a fish in its beak. Mughal. British Museum

In the past I have authored posts on, Bejeweled Maharaja & Maharani of Mysore, Koh-i-Noor Diamond, Diamonds on World Postage Stamps, Top Ten - Largest Diamonds Discovered In The World, Splendors of Mughal India, The Magnificent Maharajas Of India, Mystery & History Of Marquise Diamond Cut, Ór - Ireland's Gold, The Legendary Cullinan Diamond, Bejeweled Persia - Historic Jewelry From The Qajar Dynasty, Famous Heart-Shaped Diamonds, Type II Diamonds, Green Diamonds, Red Diamonds and more. Over years, I have spent countless hours in self-driven studies on diamond, jewelry history and research. I wrote these blogs for a simple reason - to share my collected knowledge with all who are interested, so that more can benefit from it. Take a look and enjoy! -- Reena

![The Taj Mahal Diamond [circa 1621] - a diamond with extraordinary provenance! Owned by Jahangir, ruler of Mughal India and father of Shah Jahan who built the Taj Mahal. The Taj Mahal diamond was gifted by Richard Burton to Elizabeth Taylor for her 4…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/518ee9e6e4b02c1428e17e12/1371739932987-G4G72Q5KAZQRODUFTHEH/Taj+Mahal+Diamond.jpg)