The world’s most famous, Koh-i-Noor is a diamond of monumental stature.

No other diamond in history can lay claim to be more famous, widely traveled and controversial, all at once. Today, the Koh-i-Noor remains one of the most coveted and enigmatic jewels in the world. Formed billions of years ago beneath the Earth's surface, this epic gem has witnessed 750 years of human history, weaving an extraordinary tale.

It was said whoever possessed the Koh-i-Noor would have the world's power, earthly beauty and prestige.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond, meaning "Mountain of Light" in Persian, is a legendary diamond of Indian origin. The diamond has been a subject of desire, intrigue and conquests for centuries. A widely traveled gem, it has passed through the hands of the Mughals emperors, Persian Shahs, Emirs of Afghanistan and Maharajas of Punjab. The stone later ended up in the British Crown Jewels in 1849, when a ten-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh was persuaded to hand over the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria when the Punjab Region of India was annexed. Since then, Koh-i-Noor has remained in the British Crown Jewels, becoming a symbol that many attach to the humiliation and pain of colonial past, conquests and the British Raj.

More on the lore and history of Koh-i-Noor soon. Before that, my personal connection to the Koh-i-Noor:

My connection to Koh-i-Noor is perhaps similar to children growing up in Asia (I was born in India) hearing about the lore and star-status of the Koh-i-Noor. My mother would call my siblings and I, her “Koh-i-Noor”. Her expression simply means that we are her most precious gems.

I grew up and became a jewelry designer and artist with complete love for the art, history and stories that diamonds carry. During my career, I have the privilege to hold some of the most coveted and historic diamonds. But not the elusive Koh-i-Noor. For as long as I can remember, I knew, I had to paint the Koh-i-Noor - a lifelong goal, it was destined to be.

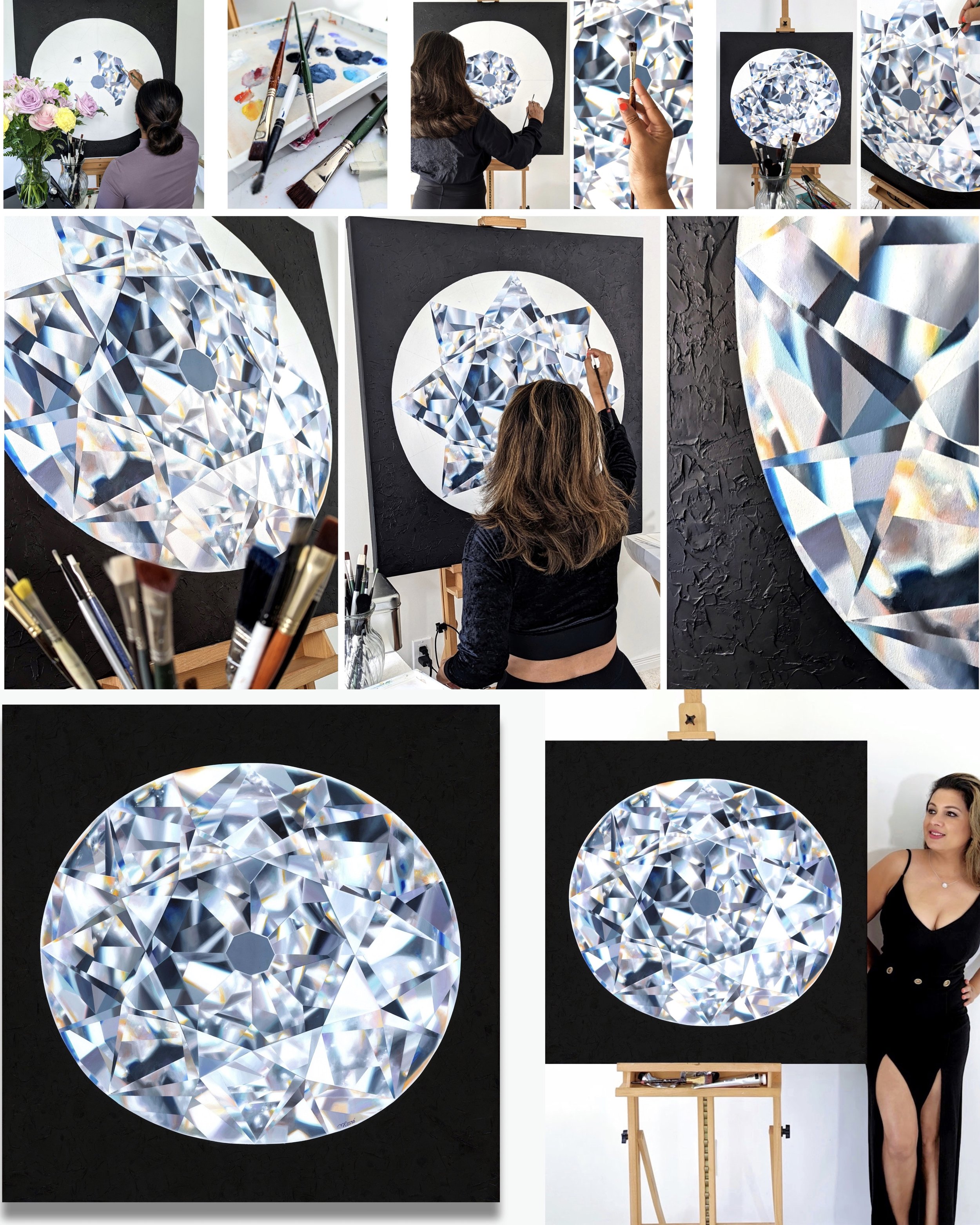

It’s 2023, and I have finally completed my Koh-i-Noor painting. What you are looking at is the closest, detailed interpretation of Koh-i-Noor diamond in an artwork in history:

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond painting on canvas by Reena Ahluwalia. What you are looking at is the closest, detailed interpretation of Koh-i-Noor diamond in an artwork in history. Image: ©Reena Ahluwalia.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond painting on canvas by Reena Ahluwalia. What you are looking at is the closest, detailed interpretation of Koh-i-Noor diamond in an artwork in history. I spent two+ years studying, researching and painting the Koh-i-Noor. You will be surprised to find that clear images of Koh-i-Noor do not exist. So in a way, I had to imagine how the real Koh-i-Noor looks like. My knowledge and life spent working with diamonds came handy. Image: ©Reena Ahluwalia.

Very few historic illustrations of Koh-i-Noor exist - that means my interpretation is imagination combined with my diamond knowledge, specifically how light should reflect on facets considering its geometry. Diamond geometry plays a huge part in how the diamond facets reflect light. It's super nuanced - a bit of art, science and math. As I painted the Koh-i-Noor, I had to constantly negotiate these factors and use my best judgement. More importantly, to capture it's true essence, symbolic stature and power.

The Koh-i-Noor is more than a gem, it's a powerful concept deeply ingrained in the identities of millions.

Making of the Koh-i-Noor diamond painting by Reena from 2021 to 2023. Images: Reena Ahluwalia.

THE KOH-I-NOOR DIAMOND ON THE BLOCKCHAIN

"As an artist, my goal is to preserve the legend and legacy of the Koh-i-Noor. Through my painting on canvas and its imprint on the blockchain as a digital artwork, I want to ensure its perpetuity. I want to return the Koh-i-Noor to the people, to everyone who feels it rightfully belongs to them. After all, when you think about it, it truly does." ~ Reena Ahluwalia, Artist.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond on blockchain is a digital artwork NFT created by artist Reena Ahluwalia. Hand-painted and 3D animated, limited edition NFT. Created: 2023. ©Reena Ahluwalia.

In my artwork, the Koh-i-Noor shines brightly as it travels across mountain terrains, symbolizing the idea of pursuit. It represents an eternal allure for the world's most enigmatic gem, sometimes within reach and sometimes distant. This mirrors the notion that what we focus on expands and flourishes. By manifesting our desires, we align ourselves with the universal law of attraction and shape our destiny.

・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥・・❥

THE HISTORY OF KOH-I-NOOR

THE KOH-I-NOOR DIAMOND

Rough Carat Weight: 793 carats

Polished Carat Weight: 105.6 carats

Color: D (colourless), Type IIa

Cut: Polished, Oval brilliant

Country of origin: India

Origin: Alluvial. Southern India. The Koh-i-Noor was unearthed from a dry river bed, probably in south India.

At 793-carats, Koh-i-Noor is the thirteenth largest gem-quality rough diamond ever discovered.

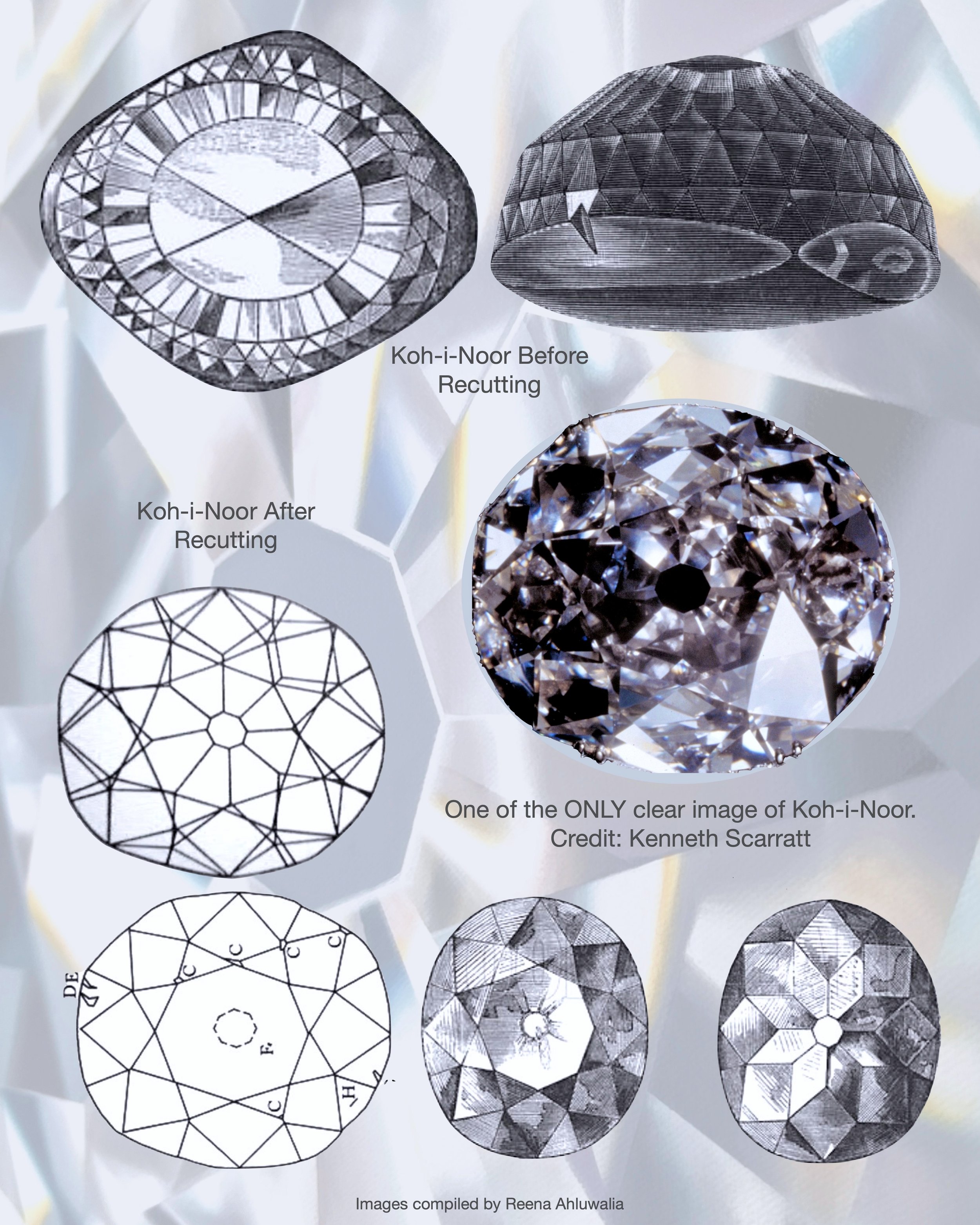

This is by far the clearest image of the Koh-i-Noor diamond thus far (June 2023, when this blog was written). Image credit: Kenneth Scarratt. Courtesy: The Gemmologists, the Crown Jewels. Kenneth Scarratt graciously shared this image with me while I was researching Koh-i-Noor for my painting.

THE KOH-I-NOOR IS A SUPERDEEP DIAMOND

Did you know? The Koh-i-Noor is an extraordinary Type IIA, “superdeep” diamond. The superdeep diamonds originate below the continental mantle keel, from a depth between 360 and 750 km. They reveal our planet's most closely guarded secrets and information about the process of subduction, when an oceanic rigid tectonic plate sinks down into the Earth. The Cullinan diamonds in the British Crown Jewels are also superdeep, "Clippir" diamonds. Read more about ‘The Very Deep Origin of the World’s Biggest Diamonds’ by Evan M. Smith, Steven B. Shirey, and Wuyi Wang [GIA].

The Koh-i-Noor is a superdeep diamond. The superdeep diamonds originate below the continental mantle keel, from a depth between 360 and 750 km. They reveal our planet's most closely guarded secrets. Image credit: F. Chirico Via Nature. Lower image by GIA, shows the cross section of the uppermost 1,000 km of the earth. Images compiled by Reena Ahluwalia.

Historic illustrations of the Koh-i-Noor diamond and the one of the only clear image of Koh-i-Noor (so far, May 2023) was taken by Kenneth Scarratt , a notable British gemologist, pearl expert, authority on the British crown jewels. Images compiled by Reena Ahluwalia.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond before re-cutting in 1852.

Diamonds are potent objects of desire.

Diamonds were a mythical substance of great legend and lore throughout history. Found in India around 4th century BC, diamonds were India's first exports and found their way to Egypt, Rome and China and Venice’s medieval markets. By the 1400s, diamonds were becoming fashionable accessories for Europe’s elite. In the early 1700s, as India’s diamond supplies began to decline, Brazil emerged as an important source.

Queen Elizabeth I, The Queen Mother's Crown. The Koh-i-Noor set crown was created for Queen Elizabeth for the coronation of King George VI on 12 May 1937. Image: The Royal Collection Trust.

THE ORIGIN AND LORE OF KOH-I-NOOR

It was said whoever possessed the Koh-i-Noor would have the world's power, earthly beauty and prestige.

It was believed that the Koh-i-Noor was sifted deep from within earth in Southern India in antiquity.

The lore has it that the gem was taken and placed in an eye of an idol in one of the temple of the Kakatiya dynasty in India (Deccan region in present-day India between 12th and 14th centuries). Many devout Hindus believe that Lord Krishna was the first owner of the diamond and the Koh-i-Noor diamond is the mythical Syamantaka gem (Sanskrit: स्यमन्तक), mentioned in 10th century ‘Bhagawat Purana’ that talks about the gem to be an intense object of desire.

Over the centuries, many devout Hindus believe the Koh-i-Noor diamond is the mythical Syamantaka gem (Sanskrit: स्यमन्तक), mentioned in 10th century ‘Bhagawat Purana’ that talks about the gem to be an intense object of desire. Thus came the association Hindus attached to Lord Krishna with the Koh-i-Noor (believed to be the Syamantaka gem). Image: Krishna being given the legendary Syamantaka gem. From a Bhagavad Purana manuscript, Rajasthan, c. 1522—1540.

As the lore goes, from there the stone was assumed to be looted from the temple’s idol by the Turks invading the region. The stone then fell in the hands of the emperors of the Ghori dynasty, then to the Tughlaq, Syed and Lodhi dynasties, and eventually to the Mughals, where it remained in their possession until the reign of Mohammad Shah ‘Rangila’, who allegedly wore it in his turban. When the Mughal empire crumbled, Mohammed Shah was said to have swapped the turban with Persian warlord Nader Shah, thus becoming his property, as goes the lore. However, history, records this incident otherwise.

Mughal school miniature painting of Muhammad Shah and Nader Shah. Muhammad Shah (1702-1748), Indian emperor, and Nader (Nadir) Shah (1688-1747), shah of Iran. Miniature painting by an unknown artist of the Mughal school. Image: Musee Guimet, national museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France.

The turban (Koh-i-Noor) swapping incident is a myth. The Koh-i-Noor was set atop the Peacock Throne at this point in history, as recorded by Muhammad Kazim Marvi of the 1739 invasion of Northern India by Nader Shah.

As you read the paragraphs above, keep in mind, the first verifiable historic reference of the diamond comes from a Persian historian, Muhammad Kazim Marvi of the 1739 invasion of Northern India by Nader Shah (Nadir Shah). Marvi notes the Koh-i-Noor as being one of many stones on the Mughal Peacock Throne that Nader Shah looted from Delhi. According to Marvi's eyewitness account, the Emperor Mohammad Shah Rangila could not have hidden the gem in his turban, because it was at that point a centrepiece of the most magnificent and expensive piece of furniture ever made: Shah Jahan's Peacock Throne. Marvi writes: "An octagon with circular brim, had its sides & canopy gilded & studded with jewels. On top of this was placed a peacock made of emeralds and rubies; on to its head was attached a diamond the size of a hen’s egg, known as the Koh-i-Noor – the Mountain of Light. Its price no one but God Himself could know!” [Paraphrased, source: William Dalrymple, Anita Anand]

A gemstone that witnessed Mughal history

The Koh-i-Noor was set in the Peacock Throne, the world’s most expensive gem-set throne. Set atop the Peacock Throne, the Koh-i-Noor witnessed reigns of many Mughal emperors - Shah Jahan (commissioned the Peacock Throne in 1628), Aurangzeb, Bahadur Shah I, Jahandar Shah, Farrukhsiyar, Rafi Ul-Darjat, Rafi Ud-Daulat, Nikusiyar, Muhammad Ibrahim and Muhammad Shah ‘Rangila’, who eventually lost the Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor diamond in an invasion-loot by Nader Shah of Persia in 1739.

The Peacock Throne

(Hindustani: Mayūrāsana, Sanskrit: मयूरासन, Urdu: تخت طاؤس, Persian: تخت طاووس, Takht-i Tāvūs)

Portrait of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan on the bejewelled Peacock Throne. 19th century. Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. In 1628, Mughal ruler Shah Jahan commissioned this magnificent, gemstone-encrusted throne. Among the many precious stones that adorned the throne were two particularly enormous gems that would, in time, become the most valued of all: the Timur Ruby—more highly valued by the Mughals because they preferred colored stones—and the Koh-i-Noor diamond. According to eyewitness account of Persian historian, Muhammad Kazim Marvi, of the 1739 invasion of Northern India by Nader Shah, Marvi notes: “On top of this was placed a peacock made of emeralds and rubies; on to its head was attached a diamond the size of a hen’s egg, known as the Koh-i-Noor – the Mountain of Light.”

Their is no historic mention, or evidence of the Koh-i-Noor in the texts or manuscripts before 1740 that can prove the origin stories, or how and when it entered the Mughal treasury, even though Mughals were excellent in recording the gems of their Toshakhana (Treasury). The stories, at best, are mythologized versions. Nevertheless, they exists, and propagate the myth and legend of the incomparable Koh-i-Noor.

According to French gem merchant and traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, who was given permission from Mughal emperor Aurangzeb to see his private collection of jewels, the stone cutter, Hortensio Borgio, had indeed brutally cut a large diamond, resulting in a sad loss of size. But he identified that diamond as the Great Mughal Diamond (Not Koh-i-Noor) that had been gifted to Mughal king Shah Jahan by diamond merchant Mir Jumla.

Most modern scholars are now convinced that the Great Mughal Diamond is actually the Orlov, today part of Catherine the Great's imperial Russian sceptre in the Kremlin.

Since the other great Mughal diamonds have largely been forgotten, all mentions of extraordinary Indian diamonds in historical sources have retrospectively come to be assumed to be references to the Koh-i-Noor. [Source: BBC]

Nadir Shah’s Invasion of India

A firework display for Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah. 1730. Opaque watercolour on paper. Image: British Museum. The decline of the Mughal dynasty reached a low ebb under Muhammad Shah (r. 1719-48) who preferred the company of his harem and amusements usch as firework displays to the rigours of battle. As a result, Delhi was easy prey for Nadir Shah of Iran who sacked it in 1739 and carried off the Peacock Throne and the Koh-i-Noor diamond along with it.

Nadir Shah and His Court. India or Iran, 18th century. Image: Christie’s. Oil on canvas, the richly adorned Nadir Shah wears a black robe and leans back against a pearl-embroidered bolster cushion upon a jewelled carpet, court officials and attendants stand around him. Nadir Shah Afshar (1688-1747), the founder of the Afsharid dynasty, deposed the last members of the Safavid dynasty in 1736, installing himself as ruler. A brilliant military leader, he quickly restored territories lost to Afghan, Ottoman and Russian armies and by 1739 he had conquered the Mughal Empire and took away the bejeweled Peacock Throne set with the Koh-i-Noor diamond as war-loot.

Portrait of Nadir Shah. 1780-1800. This is one of only two portraits of Nadir Shah in oils that survive, but they both seem to date from the late 18th century, several decades after his death. The Shah is shown wearing weapons and other accoutrements (armbands, belt, hat band etc.) that are jewelled with precious stones understood to be from the Mughal treasure. The carpet on which he sits is also Mughal. Image credit: ©Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Persian ruler Nader Shah seated on the Peacock Throne after his defeat of Muhammad Shah. Image: 1850, San Diego Museum of Art. The Peacock Throne was set with one of the most coveted diamonds - the Koh-i-Noor. In 1739, the Persian ruler Nader Shah swept into Delhi and conquered the capital in a frenzy of carnage. The Peacock throne – with the Koh-i-Noor embedded in it – left India, carried into Persia on the backs of thousands of elephants, camels and horses. Back in Khorasan, Nader Shah stripped the throne of two of its greatest jewels – the Koh-i-Noor and an exquisite ruby – and wore them around his arms.

The Koh-i-Noor, which weighed 190.3 metric carats when it arrived in Britain, had had at least two comparable sisters, the Darya-i-Noor, or Sea of Light, now in Tehran, and the Great Mughal Diamond, believed by most modern gemologists to be the Orlov diamond. All three diamonds left India as part of Iranian ruler Nader Shah's loot after he invaded the country in 1739.

Koh-i-Noor in Afghanistan

After Nader Shah’s death, the Koh-i-Noor passed to his Afghan bodyguard Ahmed Shah Abdali, the stone spent next 100 years in Afghanistan, before Maharaja Ranjit Singh extracted it from fleeing Afghans in 1813.

Ahmad Shah Durrani (also known as Ahmad Shah Abdali) was the founder of the Durrani Empire in Afghanistan. After Ahmad Shah Durrani, the Koh-i-Noor passed onto his grandson Zaman Shah Durrani. His younger brother Shah Shujah Durrani then had the gem and traded it to Ranjit Singh in exchange for respite after losing his family empire. [It reveals some unexpected and previously unknown moments in the diamond's history, such as the months the diamond spent hidden in a crack in the wall of a prison cell in a remote Afghan fort, and the years during which it languished unrecognised and unvalued on a mullah's desk, used only as a paperweight for pious sermons. [Source: William Dalrymple]

Painting of Ahmad Shah Abdali (also known as Ahmad Shah Durrani). Founder of the Durrani Empire, King of Afghanistan from 1747 until his death. Image: Lahore Museum. 1755.

It was only in the early 19th Century, when the Koh-i-Noor reached the Punjab, that the diamond began to achieve its preeminent fame and celebrity.

Enter, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, popularly known as Sher-e-Punjab or Lion of Punjab.

It was not just that Ranjit Singh liked diamonds, and respected the stone’s vast monetary value; the gem seems to have held a far greater symbolism for him. Since he had come to the throne he had won back from the Afghan Durrani dynasty almost all the Indian lands they had seized since the time of Ahmad Shah. Having conquered all the Durrani territories as far as the Khyber Pass, Ranjit Singh seems to have regarded his seizure of the Durrani’s dynastic diamond as his crowning achievement, the seal on his status as the successor to the fallen dynasty. It may have been this, as much as the beauty of the stone, that led him to wear it on his arm on all state occasions. [Source: William Dalrymple / OutlookIndia]

Painting of Sikh Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Indian school 19 century. Image credit: The Royal Collection Trust. Maharaja Ranjit Singh is seen wearing the Koh-i-Noor set in his armband as an armlet. “Of all the owners of the Koh-i-Noor,” Historians Anita Anand and William Dalrymple write, “none made more of the diamond than Ranjit Singh”, who turned it into a symbol of his rule.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh is seen wearing the Koh-i-Noor set in his armband as an armlet.

Drawing of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond armlet by R. S. Garrard & Co. 1851. Image: Met Museum.

Front view. Garrard & Co replica with rock crystal replica of the Koh-i-noor armlet, as worn by Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Duleep Singh. 1830. Image credit: The Royal Collection Trust.

Back view. Garrard & Co replica with rock crystal replica of the Koh-i-noor armlet, as worn by Maharaja Ranjit Singh and Duleep Singh. 1830. Image credit: The Royal Collection Trust.

The Koh-i-Noor in the British Crown Jewels

When the British learned of Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, and his plan to give the diamond and other jewels to a sect of Hindu priests, the British press exploded in outrage. “The richest, the most costly gem in the known world, has been committed to the trust of a profane, idolatrous and mercenary priesthood,” wrote one anonymous editorial. Its author urged the British East India Company to do whatever they could to keep track of the Koh-i-Noor, so that it might ultimately be theirs. For the British, that symbol of prestige and power was irresistible. If they could own the jewel of India as well as the country itself, it would symbolize their power and colonial superiority. It was a diamond worth fighting and killing for, now more than ever. [Source: Smithsonian]

The stone eventually ended up in the British Crown Jewels in 1849, when a ten-year-old Maharaja Duleep Singh was forced to hand over the Koh-i-Noor to Queen Victoria when the Punjab Region of India was annexed.

After Ranjit Singh’s death in 1839, the Punjab throne passed between four different rulers over four years. At the end of the violent period, the only people left in line for the throne were a young boy, Duleep Singh, and his mother, Rani Jindan. And in 1849, after imprisoning Jindan, the British forced Duleep to sign a legal document amending the Treaty of Lahore, that required Duleep to give away the Koh-i-Noor and all claim to sovereignty. The boy was only 10 years old. Image: Getty Image.

When he heard that Duleep Singh had finally signed the document, the Scottish Governor-General, James Broun-Ramsay, Lord Dalhousie, was triumphant. “I have caught my hare,” he wrote. He later added: “The Koh-i-Noor has become in the lapse of ages a sort of historical emblem of the conquest of India. It has now found its proper resting place.” On a cold, bleak day in December, Dalhousie arrived in person in Lahore to take formal delivery of his prize from the hands of Duleep Singh and his Scottish guardian, Dr Login. Still set in the armlet which Maharaja Ranjit Singh had worn, the Koh-i-Noor was removed from the safe of the Lahore Toshakhana, or Treasury, by Dr Login, and placed in a small bag which had been specially made by Lady Dalhousie. Broun-Ramsay wrote out a receipt: “I have received this day the Koh-i-Noor diamond.” [Source: William Dalrymple]

James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie, also known as Lord Dalhousie, was the Governor-General of India (1848-1856) East India Company. Under his rule the Punjab became a British province and further territories were annexed; introduced the railway and telegraph to India; his policies much criticized after the outbreak of the Mutiny in 1857. In 1849, under Dalhousie's command, the British captured the princely state of Punjab. In the process he captured the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond from the ten-year old Punjabi Maharaja Duleep Singh. The treasury of Duleep Singh was considered war booty and Duleep Singh was forced to hand over the diamond. The Koh-i-Noor diamond was presented to Queen Victoria.

Lord Dalhousie visits the young Maharaja Duleep Singh. Lahore, 1845. Credit: The Toor Collection.

Separating history from myth

After the Koh-i-Noor came into the hands of the British East India Company’s Governor-General Lord Dalhousie in 1849, he prepared to have it sent, along with an official history of the stone, to Queen Victoria. Dalhousie commissioned Theo Metcalfe, a junior assistant magistrate in Delhi with a taste for gambling and parties, to undertake some research on the gem. But Metcalfe accumulated little more than colourful bazaar gossip that has since been repeated in article after article, book after book, and even sits unchallenged on Internet today as the true history of the Koh-i-Noor. [Source: BBC]

"So much of the tale about this diamond, which has been repeated over and over again over the last century and a half, is completely unsubstantiated. Contrary to the myths it retells, there are no hard, certain references to the diamond before it sat atop the Peacock Throne”(as recorded by Persian historian, Muhammad Kazim Marvi in 1739). [Source: William Dalrymple]

Portrait of Maharaja Duleep Singh. Commissioned by Queen Victoria in 1854 by artist Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Image credit: The Royal Collection Trust. The Koh-i-Noor diamond’s last Indian owner was Duleep Singh. Named Maharaja of Lahore at the age of five and deposed at the age of 10, he was raised by Scottish guardians, converted to Christianity and, in his teens, moved to Britain where he became a special favourite of Queen Victoria’s.

Queen Victoria (1819-1901) wearing the Koh-i-Noor diamond set in a brooch. Oil painting by Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1856. Image: Royal Collection Trust.

Maharaja Duleep Singh, photographed by John Jabez Edwin Mayall in 1861. Image credit: The Royal Collection Trust.

Portrait of maharani Jind Kaur, wife of Maharaja Ranjit Singh and mother of Maharaja Duleep Singh. 1863. George Richmond.

Maharajah Duleep Singh. 1885, Bombay, India. Image: Peter Bance Collection. In his 20s Duleep’s traumatic dispossessions began to tell. He reconnected with his exiled mother, married a woman of whom Victoria disapproved, and lapsed into dissolution. In the 1880s, bankrupt and renounced by the Queen, he sailed for India to pursue a misbegotten plot to reclaim Punjab with Russian support. He was arrested en route and died in poverty a few years later.

In 1849, Koh-i-Noor diamond became a special possession of Queen Victoria. It was displayed at the 1851 Great Exposition in London, only for the British public to be dismayed at how simple it was. “Many people find a difficulty in bringing themselves to believe, from its external appearance, that it is anything but a piece of common glass,” wrote The Times in June 1851. Given its disappointing reception, Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, had the stone recut and polished—a process that reduced its size by half but made the light refract more brilliantly from its surface. [Source: Smithsonian]

Great Exposition in London where Koh-i-Noor made it’s British public appearance. 1851. Eager to see the famous gem, six million people, one-third of the Britain's population, queued up for a glimpse.

Great Exposition in London where Koh-i-Noor made it’s British public appearance. 1851.

Koh-i-Noor’s Mughal Cut, pre-British recutting

An exact replica of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond, before recutting. Image: The Natural History Museum, London, UK. The Koh-i-Noor was shaped in the Mughal cut before re-cutting. The Natural History Museum in London created a plaster mold of the diamond in 1851, prior to the recutting, and from this two plaster casts were made. The two plaster casts are the only replicas known to have been made from the original stone (a cubic zirconia [CZ] replica has been cut based on one of these plaster forms, as described in Hatleberg, 2006, but no details as to the specific techniques used were provided in that report). One of the plaster casts is on permanent display at the museum. The term Mughal Cut describes a diamond cut in India in the 16th, 17th or 18th century.

THE USE OF LASER AND X-RAY SCANNING TO CREATE A MODEL OF THE HISTORIC KOH-I-NOOR DIAMOND by Scott D. Sucher and Dale P. Carriere, as appread in the Summer 2018, Gem & Gemology, GIA.

Replica of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond by John Nels Hatleberg who creates precise reproductions of iconic diamonds. For many years, John would “chase certain gems.” When he discovered that there was a plaster cast of the original Koh-i-Noor diamond in the Natural History Museum in London, he became determined to get permission to work on it. It took 13 years for him to get the okay from the museum to craft the replica. He completed it in 2005. The project was challenging, he says, because “of the four facets of the stone that meet in the center and the ratio of the length to the width. I essentially locked myself away and cut the whole thing in six months.” [Source: Jewelry Connoisseur | Rapaport]

The Koh-i-Noor was shaped in the Mughal cut before re-cutting.

Replica of the Koh-i-Noor diamond, Falcon Glassworks of Apsley Pellatt & Co., 1851. Colorless lead glass, 1 × 2.4 × 2.2 in. Gift of Dr. Julius and Dena K. Tarshis, Collection of The Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY. The Koh-i-Noor was shaped in the Mughal cut before re-cutting.

Re-cutting of the Koh-i-Noor in 1852

When the diamond arrived in England in 1850, it was reported to have weighed 186 old carats. It was poorly cut with a flat base and set in an armlet. In 1852, largely on the suggestion of Prince Albert, the Koh-i-noor was recut for Queen Victoria, which resulted in a significant loss of weight. Today, the diamond is an oval modified brilliant cut that weighs 105.60 modern carats.

Coster Diamonds, an Amsterdam diamond polishing factory, owned by Martin Coster was entrusted to repolish the Koh-i-Noor. Martin Coster sent two of his best master polishers to London, Levi Benjamin Voorzanger and Joseph Abraham Fedder. In London, Voorzanger and Fedder installed a steam engine that was similar to the ones they had in Amsterdam. On 16 July 1852, they started their Royal task. After almost two months, they finished on 7 September 1852.

RE-CUTTING IN 1852. The Koh-i-Noor, before re-cutting. Image: Hulton Archive.

Originally, the diamond had 169 facets and was 4.1 centimetres (1.6 in) long, 3.26 centimetres (1.28 in) wide, and 1.62 centimetres (0.64 in) deep. It was high-domed, with a flat base and both triangular and rectangular facets, similar in overall appearance to other Mughal-era diamonds which are now in the Iranian Crown Jewels.

On 17 July 1852, the cutting began at the factory of Garrard & Co. in Haymarket, using a steam-powered mill built specially for the job by Maudslay, Sons and Field. Under the supervision of Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington, and the technical direction of the queen's mineralogist, James Tennant, the cutting took thirty-eight days. Albert spent a total of £8,000 on the operation, which reduced the weight of the diamond from 186 old carats (191 modern carats or 38.2 g) to its current 105.6 carats (21.12 g). The stone measures 3.6 cm (1.4 in) long, 3.2 cm (1.3 in) wide, and 1.3 cm (0.5 in) deep. Brilliant-cut diamonds usually have fifty-eight facets, but the Koh-i-Noor has eight additional "star" facets around the culet, making a total of sixty-six facets.

While Victoria wore the diamond as a brooch, it eventually became part of the Crown Jewels, first in the crown of Queen Alexandra (the wife of Edward VII, Victoria’s oldest son) and then in the crown of Queen Mary (the wife of George V, grandson of Victoria). The diamond was set in the crown worn by the Queen Mother, wife of George VI and mother of Elizabeth II in 1937. The crown made its last public appearance in 2002, resting atop of the coffin of the Queen Mother for her funeral. [Source: Smithsonian]

The Koh-i-Noor set in Queen Alexandra’s Crown in 1902. The Coronation of King Edward VII. Image: W. and D. Downey.

Replica of crystal Koh-i-Noor diamond in Queen Marys Crown. 1911. Image: The Royal Collection Trust.

The Koh-i-Noor set crown worn by Queen Mary on Coronation Day of King George V. June 1911. Image: Hulton Archive, Getty images.

The crystal replica of Koh-i-Noor diamond in Queen Marys Crown. 1911. The Royal Collection Trust.

The Koh-i-Noor set crown worn by Queen Mother, Elizabeth I at George VI’s Coronation on 1923.

Queen Elizabeth I, The Queen Mother's Crown. The Koh-i-Noor set crown was created for Queen Elizabeth for the coronation of King George VI on 12 May 1937. Image: The Royal Collection Trust.

Left, the Koh-i-Noor made an appearance during the coronation of King George VI worn by his wife, Queen Mother, Elizabeth I. May 12, 1937. Image: Corbis via Getty Images.

The Koh-i-Noor diamond last made a public appearance in April 2002, when the crown was placed on top of the Queen Mother’s coffin at her funeral.

Koh-i-Noor and the myth of a cursed gem

It was said whoever possessed the Koh-i-Noor would have the world's power, earthly beauty and prestige. The tales of curse stems from the story of Saymataka Gem in 10th century Bhagawat Purana, that talks about the gem to be an intense object of desire, that whoever came close, the desire will end up with some sort of problems. The stories of curse are fiction, but if you look at anyone who holds something of great beauty and value, as a result will have envy, jealousy and in the past centuries, a battle or conquest. All this made up the myth that the Koh-i-Noor was cursed. If you look at many historic gems, the lore suggests they were cursed - it does make for a good story. The superstition that only women can wear it, was propagated by Theo Metcalfe - and by the time it was the coronation of British King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra, the superstition was set. [Source: William Dalrymple]

In 2023, the coronation of King Charles III saw the disappearance of the Koh-i-Noor as part of the regalia and coronation ceremony.

According to the Buckingham Palace, Queen Mary’s Crown was merely being recycled in the “interests of sustainability and efficiency”. But the separation of the Koh-i-noor from the crown that has cradled it for the past 86 years feels significant in what it says about shifting attitudes to empire and royalty. Throughout history, diamonds and other precious stones have played an integral role in displays of political power, so swapping one gem for another is no trivial matter.

The Koh-i-Noor’s absence from Queen Camilla’s crown is an important moment. While the history of the monarchy’s evolution, entwined with empire, was once a matter of little interest, global public opinion has shifted powerfully in the last decade towards scrutiny of empire and its long legacies. [Source: FT]

Coronation of King Charles III in 2023. Queen Consort Camilla wore Queen Mary's Crown with the Cullinan III, IV and V diamonds that were part of Queen Elizabeth's personal jewelry collection. What was removed from the crown was the world's most famous and controversial diamond - the legendary Koh-i-Noor. Queen Camilla was also wearing the Coronation necklace made for Queen Victoria by Garrard & Co.

Coronation of King Charles III. 2023. Queen Consort Camilla wore Queen Mary's Crown, now set with Cullinan III, IV and V diamonds that were part of Queen Elizabeth's personal jewelry collection. The current crown excludes the Koh-i-Noor diamond.

The 105.6 carat Koh-i-Noor diamond has a highly conflicted and colonial past, including how it came to be included in the British crown jewels. The Koh-i-Noor has long been a subject of diplomatic controversy, with India, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan all demanding its return from the UK at various points.

The diamond isn’t likely to leave the Crown Jewels anytime soon. However, now, with more light being shed into the path that gemstone has followed thought out the recorded history, it may help leaders come to their own conclusions about what to do with it next with it’s ownership status and repatriation claims. Ownership of the gem is a highly emotional issue for many Indians, who believe it was stolen from them by the British.

So what’s next for the Koh-i-Noor?

A new exhibition at the Tower of London featuring the Crown Jewels will describe the controversial Koh-i-noor diamond as a “symbol of conquest”. The display, which opened to the public on May 26, 2023, weeks after the coronation of King Charles III and Queen Consort Camilla, will explore the origins of some of the jewels for the first time. The history of the Koh-i-noor, which is set within the coronation crown of the Queen Mother, will be explored using a combination of objects and visual projections to explain the stone's story as a “symbol of conquest”. This, according to the Buckingham Palace.

The new Jewel House exhibition which displays the Kohinoor diamond, at the Tower of London. The 'Origins' room (above) tells the stories behind the Koh-i-Noor diamond. Exhibit is sponsored by Garrard at the Jewel House in the Tower of London. Image: Historic Royal Palaces

The new Jewel House exhibition acknowledges the “incredibly complex story” of Koh-i-Noor for the first time, said its curator ,Charles Farris, a public historian at Historic Royal Palaces. New information boards, developed in consultation with British academics, call the Koh-i-noor a “symbol of conquest” and state that “the 1849 Treaty of Lahore compelled [Singh] to surrender it to Queen Victoria, along with control of the Punjab”. [Source: The Guardian]

Even though the legendary Koh-i-Noor diamond is removed from the crown and being added to an exhibition as a "symbol of conquest", it will continue to remain an object of desire, mystery, conquest and unbridled beauty in people's imagination for centuries to come.

The story of Koh-i-Noor is far from over.

Making of the Koh-i-Noor Diamond painting on canvas by artist Reena Ahluwalia. Image: ©Reena Ahluwalia.

The Koh-i-Noor Diamond painting on canvas by artist Reena Ahluwalia. What you are looking at is the closest, detailed view and interpretation of Koh-i-Noor diamond in an artwork in history. Image: ©Reena Ahluwalia.

———

Acknowledgement

To learn about the detailed history of Koh-i-Noor diamond, I recommend this book: Koh-i-Noor: The History of the World's Most Infamous Diamond by William Dalrymple and Anita Anand. I am thankful to the contributions of William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, without their research into the history of Koh-i-Noor, this educational blog wouldn’t be possible. If you want to listen to podcast episodes on Koh-i-Noor Diamond, visit the Empire Podcast : Here.

In the past I have authored posts on, Bejeweled Maharaja & Maharani of Mysore, Diamonds on World Postage Stamps, Top Ten - Largest Diamonds Discovered In The World, Splendors of Mughal India, The Magnificent Maharajas Of India, Mystery & History Of Marquise Diamond Cut, Ór - Ireland's Gold, The Legendary Cullinan Diamond, Bejeweled Persia - Historic Jewelry From The Qajar Dynasty, Famous Heart-Shaped Diamonds, Type II Diamonds, Green Diamonds, Red Diamonds and more. Over years, I have spent countless hours in self-driven studies on diamond, jewelry history and research. I wrote these blogs for a simple reason - to share my collected knowledge with all who are interested, so that more can benefit from it. Take a look and enjoy! -- Reena