May the rocks in your field turn to gold. -- Irish blessing

Glorious gold! It dazzled me on my recent visit to Dublin, Ireland. I was awestruck! The gold-work history is fascinating and so are the forms and textures. Hope you enjoy this blog post as much as I enjoyed learning about the history of gold in Ireland!

The National Museum of Ireland's collection of prehistoric gold-work, ranging in date between 2200 BC and 500 BC, is one of the largest and most important in western Europe. Most are pieces of jewellery but the precise function of some is unknown.

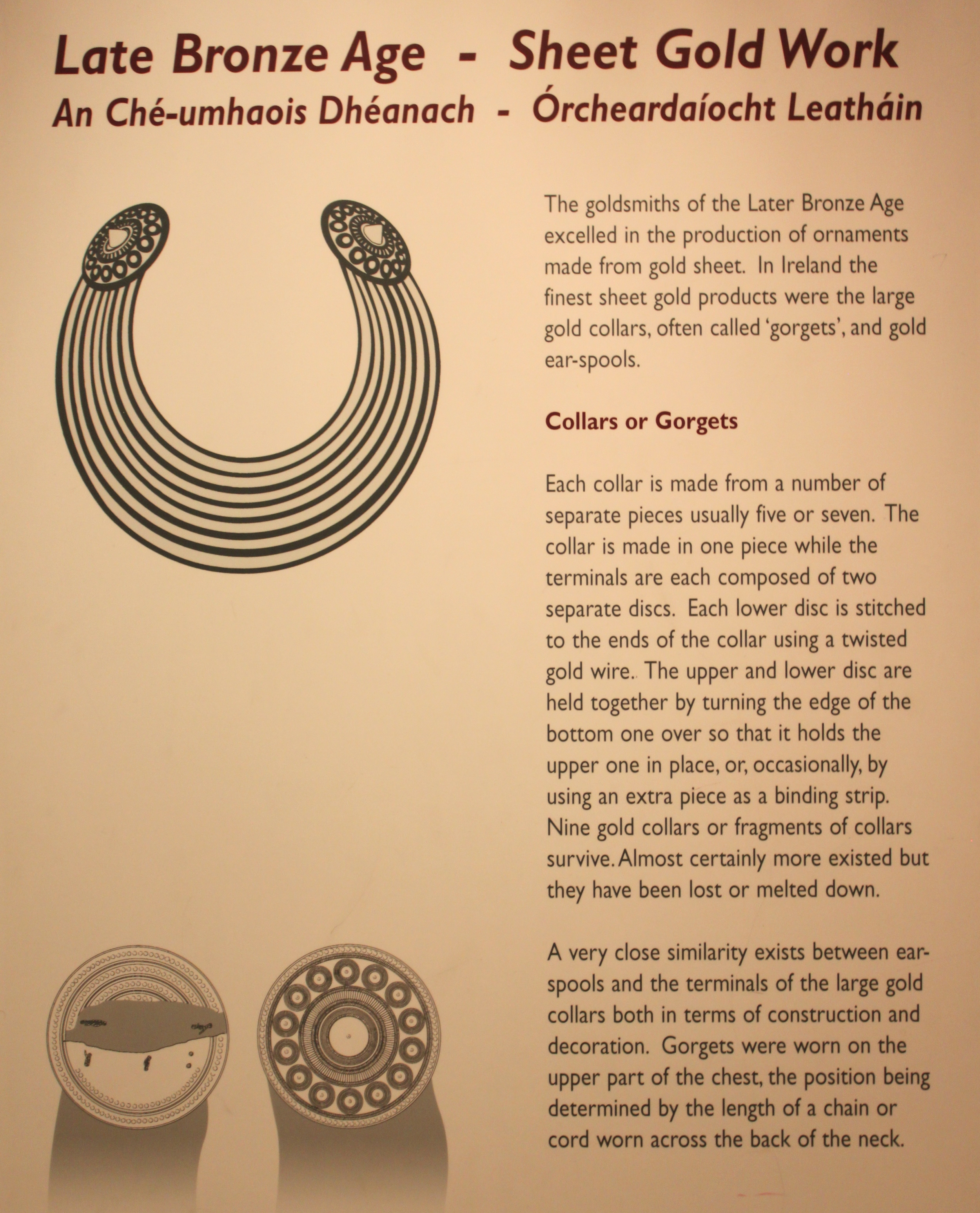

During the Early Bronze Age the principal products were made from sheet gold, and include sundiscs and the crescentic gold collars called lunulae. Around 1200 BC new gold working techniques were developed. During this time a great variety of torcs were made by twisting bars or strips of gold.

Styles changed again around 900 BC and the goldwork of this period can be divided into two main types. Solid objects such as bracelets and dress-fasteners contrast dramatically with large sheet gold collars and delicate ear-spools.

Although gold has been found in Ireland at a number of locations, particularly in Co. Wicklow and Co. Tyrone, it has not yet been possible to identify the ancient sources where gold was found. The sites most likely to have been recognized and exploited by prehistoric people are alluvial deposits from rivers and streams. This ‘placer’ gold is weathered out from parent rock and can be recovered using simple techniques such as panning.

In Europe, the earliest evidence for gold-working dates to the fifth millennium BC. By the end of the third millennium gold-working had become well established in Ireland and Britain together with a highly productive copper and bronze working industry. While we do not know precisely how the late Neolithic people of Ireland became familiar with metalworking, it is clear that it was introduced as a fully developed technique. Essential metalworking skills must have been introduced by people already experienced at all levels of production, from ore identification and recovery through all stages of the manufacturing process.

Source: National Museum of Ireland - Archaeology

Photographs shown below are taken by Reena Ahluwalia at the National Museum of Ireland, Archaeology, unless otherwise stated.

Reena Ahluwalia at the National Museum of Ireland - Archaeology. Dublin

Gold Ribbon Torc. Near Belfast. 3rd century BC. National Museum of Ireland

The Broighter Gold Collar. Concentric arches drawn by compass highlight raised decoration of S-shaped scrolls, trumpet shapes and lentoids. From the hoard of gold objects. Broighter, county Derry. 1st century BC.

The Broighter Gold Collar. From the hoard of gold objects. Broighter, county Derry. 1st century BC. Concentric arches drawn by compass highlight raised decoration of S-shaped scrolls, trumpet shapes and lentoids. Collars are especially associated with Celtic kings and gods. The sea god Manannán mac Lir was associated with Lough Foyle and may have had special significance for a local king, perhaps as a protective deity or divine ancestor.

The Tara brooch. 8th century. This brooch was found not in Tara but near the seashore at Bettystown, Co. Meath, in 1850. Its provenance was attributed to Tara by a dealer in order to increase its value. It is made of cast and gilt silver and is elaborately decorated on both faces. The front is ornamented with a series of exceptionally fine gold filigree panels depicting animal and abstract motifs that are separated by studs of glass, enamel and amber. The back is flatter than the front, and the decoration is cast. The motifs consist of scrolls and triple spirals and recall La Tène decoration of the Iron Age.

A silver chain made of plaited wire is attached to the brooch by means of a swivel attachment. This feature is formed of animal heads framing two tiny cast glass human heads. Along with such treasures as the Ardagh Chalice and the Derrynaflan Paten, the Tara Brooch can be considered to represent the pinnacle of early medieval Irish metalworkers’ achievement. Each individual element of decoration is executed perfectly and the range of technique represented on such a small object is astounding. National Museum of Ireland.

Silver Chalice, (The Ardagh Chalice). Reerasta, Ardagh, county Limerick. Ireland. 8th Century BC.

The Ardagh Chalice is one of the greatest treasures of the early Irish Church. It is part of a hoard of objects found in the 19th century by a young man digging for potatoes near Ardagh, Co. Limerick. It was used for dispensing Eucharistic wine during the celebration of Mass. The form of the chalice recalls late Roman tableware, but the method of construction is Irish. The bowl and foot of the chalice are made of spun silver. The outer side of the bowl is decorated with applied gold, silver, glass, amber and enamel ornament. The underside of the foot is also highly decorated and contains a polished rock crystal at the centre.

Detail. Silver Chalice, (The Ardagh Chalice). Reerasta, Ardagh, county Limerick. Ireland. 8th Century BC.

Detail. Silver Chalice, (The Ardagh Chalice). Reerasta, Ardagh, county Limerick. Ireland. 8th Century BC.

The Bell of St. Patrick and its Shrine. Armagh, Ireland. 8th-9th century AD. This bell is reputed to have belonged to St. Patrick. It is made of two sheets of iron which are riveted together and coated with bronze. This bell is frequently mentioned in written sources as one of the principal relics of Ireland.

An inscription on its surface indicates that the shrine for the bell was made around AD 1100. It is trapezoidal in shape, echoing the shape of the bell it was made to cover. Formed of a series of bronze plates joined at the edges by tubular bindings, the shrine is topped by a curved crest which covers the handle of the bell. The front of the shrine is covered with a silver-gilt frame that originally held thirty gold filigree panels. These are arranged in the shape of a ringed cross. The sides of the shrine are adorned with openwork panels depicting elongated beasts intertwined with ribbon-bodied snakes. The back of the shrine is plainer and flatter, and is decorated with an openwork silver plate featuring interlocking crosses. The inscription along the edge of the backplate records the name of the craftsman and his sons who made the shrine, and Domhnall Ua Lochlainn, King of Ireland between AD 1094 and 1121, who commissioned the shrine; Cathalan Ua Maelchallain, the keeper of the bell, is also mentioned. Remarkably, the shrine remained in the possession of this family until the end of the 19th century.

Side View. The Bell of St. Patrick and its Shrine. Armagh, Ireland. 8th-9th century AD.

Detail. The Bell of St. Patrick and its Shrine. Armagh, Ireland. 8th-9th century AD. This bell is reputed to have belonged to St. Patrick. It is made of two sheets of iron which are riveted together and coated with bronze.

The Cross of Cong. County, Mayo. Ireland. Early 12th century AD. The Cross of Cong represents the conclusion of a long tradition of distinctively Irish church metalwork.

It was made to enshrine a relic of the True Cross, known from written sources to have been acquired in AD 1122 by Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair (Turlough O’Conor), High King of Ireland. The cross was designed for processional use, although it may have been mostly used as an altar cross. It has an oak core which is covered by plates of cast bronze. A large polished rock crystal on the front of the cross at the junction of the arms and shaft was intended to protect the relic, which does not survive. The rock crystal is set in a conical mount surrounded by a flange decorated with gold filigree, niello and blue and white glass bosses. The bronze plates on the surfaces of the cross are cast openwork and are decorated with ribbon-shaped intertwined animals in the Scandinavian-derived Urnes style.

The inscription on the sides of the cross identifies Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair as the patron and Máel Ísú mac Bratáin Uí Echach as the craftsman. Two prominent churchmen are also mentioned. The inscription, which is in Irish, is framed by two identical lines in Latin that translate as ‘by this cross is covered the cross on which the creator of the world suffered’.

Detail. The Cross of Cong. County, Mayo. Ireland. Early 12th century AD. The Cross of Cong represents the conclusion of a long tradition of distinctively Irish church metalwork.

Example of a borrowed woodcarving technique known as kerbschnitt (German) or chip-carving. Surface of object is cut away in oblique cuts to give it a faceted look and added brilliance when gilded. National Museum of Ireland.

Example of a borrowed woodcarving technique known as kerbschnitt (German) or chip-carving. Surface of object is cut away in oblique cuts to give it a faceted look and added brilliance when gilded. National Museum of Ireland.

Gold Dress Fastener. Clones. County, Monaghan. Ireland. 800-700 BC.

Gold Dress Fastener. Clones. County, Monaghan. Ireland. 800-700 BC.

Miniature Gold Boat, as an offering to sea god. From the hoard of gold objects. Broighter, county Derry. 1st century BC.

Museum of Ireland. Irish man, late Bronze Age.

Gold Collars. 800-700 BC. National Museum of Ireland.

Gold Collar. 800-700 BC. National Museum of Ireland.

Gold Collar. 800-700 BC. National Museum of Ireland.

Gold Collar. 800-700 BC. National Museum of Ireland.

Gold disc, perhaps a terminal from a collar or ear spool. 800-700 BC. National Museum of Ireland.

Hollow gold balls. Late Bronze Age, Ireland. Graduated sizes and with holes suggest that these balls could have been strung together to form a necklace.

An Amber necklace and a gold dress fastener. 800-700 BC. Ireland.

2300 yr old mummified Bog body of Old Croghan Man, with leather and Celtic metal binding.National Museum of Ireland.

2300 yr old mummified Bog body of Old Croghan Man, with leather and Celtic metal binding.National Museum of Ireland.

Amazing to see these rings! Oldest known Claddagh rings in Ireland at Thomas Dillon Jewellers. Galway, Ireland.

Designer Reena Ahluwalia at Aran Island. Ireland. 2013

In the past I have authored posts on, Bejeweled Maharaja & Maharani of Mysore, Koh-i-Noor Diamond, Diamonds on World Postage Stamps, Top Ten - Largest Diamonds Discovered In The World, Splendors of Mughal India, The Magnificent Maharajas Of India, Mystery & History Of Marquise Diamond Cut, Ór - Ireland's Gold, The Legendary Cullinan Diamond, Bejeweled Persia - Historic Jewelry From The Qajar Dynasty, Famous Heart-Shaped Diamonds, Type II Diamonds, Green Diamonds, Red Diamonds and more. Over years, I have spent countless hours in self-driven studies on diamond, jewelry history and research. I wrote these blogs for a simple reason - to share my collected knowledge with all who are interested, so that more can benefit from it. Take a look and enjoy! -- Reena